It's been way too long since I've posted here. Life gets busy. Sigh.

Luckily, I've been working on a conversational style post with my colleague and friend Brad Dunn from the The Field Museum in Chicago. I'd like to share that here.

This back and forth originated via the Strategy Special Interest Group of the Museum Computer Network. That group had been discussing the various ways that the cultural heritage sector was dealing with digital technology - comparing across organizations things like reporting structures, job titles and even how each institution conceptualized "digital". In response to that expressed interest, Brad and I conducted a discussion over the course of a few days, working asynchronously via a shared document. I think there are some interesting tidbits in here about digital, org structure, collaboration and strategy. See if you agree:

Conversation: What and Where is Digital?

Context

Museums and cultural heritage organizations, just like companies and institutions across many other sectors, have gone through transformative changes during the internet era. Some of those changes are directly attributable to the impact of digital, others have more to do with changing workforce demographics and shifting customer preferences. As museums make these structural and philosophical adjustments, an important question becomes “What exactly is digital? Is it websites, or is it IT, or is it both? What about content and marketing? How does this all fit together?”

Because digital can mean different things to different museums, we wanted to dive into a discussion about just that, and to investigate which operational units make up digital in our museums. In addition, we wanted to understand where the digital technology staff report and why. For example, we’ve heard of museum departments that include some or all of this rather long list of operational units:

- Marketing and Communications

- Website and mobile apps

- Information Technology (IT)

- Exhibitions Interactives & Media

- Social Media

- Photo Studio

- Video Production, multimedia production

- Customer Relationship Management, Analytics & Marketing Insights

- Ticketing

- Ecommerce

- Editorial

- Design

- Digital artwork installation and maintenance

- Software development and QA

- Project management and business analysis

Whew! So let’s talk. What and where is digital in your organization?

Douglas Hegley, Chief Digital Officer, Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia)

Digital is an essential and core aspect of the entire business of museums. It cannot and must not be separated from the rest of the organization, but instead permeates and supports all operations. In addition, digital is an innovation-driven strategic partner, bringing new ideas and initiatives to the table for consideration. Therefore, digital is both service-oriented (reactive) and strategically-aligned (proactive).

Brad Dunn, Web and Digital Communications Director, The Field Museum, Chicago

Like most institutions, information technology systems and support have existed at the The Field Museum for many years. Within that group, the effort evolved to include the collections database and then the website. Over the years, a parallel effort in exhibitions led to the buildout of their capacity to produce video and interactive for exhibitions. In short, digital was located all over the building, and only in some instances different parties were collaborating. As of 2017, our efforts to remove silos continues. The disciplines we would normally think of as “digital” are still structurally disparate, and though there are definite challenges to collaboration, there is a very genuine belief in the importance of cross-discipline collaboration, and in many instances it’s starting to work very well.

Douglas:

I’m always struck by how different museums structure the work of digital. I’m not surprised that you describe a situation of organic growth - digital popping up where it’s needed, and at different moments in the organization’s timeline. It’s also fascinating to see the many different approaches to organizational structure.

Brad:

So let’s talk about that topic: organizational structure. Where does digital sit at Mia?

Douglas:

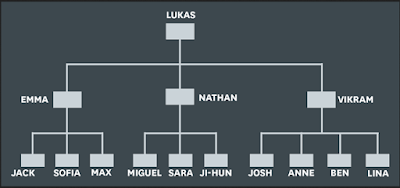

At Mia, digital sits within a division called Media and Technology (MAT). That division is made up of five departments:

- Interactive Media (digital media production, video, in-gallery interactives, time-based media art installation and maintenance)

- Visual Resources (photo studio, digital photography, photogrammetry, post-production, cataloguing, digital asset management, rights and reproductions)

- Software development (web, mobile, apps, business systems, APIs)

- Digital Strategy Implementation (project management, administration)

- Information Systems (traditional IT, telecomm, systems and networking, tech support)

In addition, two unique skillsets sit within MAT, not as departments but as individual staff:

- Content databases: collections management, standards and cataloguing of the museum collection, enterprise content planning & management

- CRM (Customer Relationship Management system - salesforce): constituent (customer, member, donor, volunteer, vendor, etc.) data collection and maintenance, customer/member validation, activity tracking, and analytics

MAT is led by me as the Chief Digital Officer. I sit on the museum’s executive leadership team, reporting to the Director/President. In that regard, digital does not sit within another department such as Marketing or IT, but is instead its own, top-level division - collaborating with all other divisions, and at the table for every major executive-level discussion and decision. In addition, IT is actually a department underneath digital, which was a strategic decision - we see digital and user engagement as the leading principles here, not technology per se.

What about at the Field Museum? How are you structured?

Brad:

The digital team is located within the Marketing and Public Engagement division, and includes the website, digital content creation, and social media and digital engagement. This team reports to me as the Web and Digital Communications Director, and I report to the Chief Marketing Officer.

This team is charged with engaging the public in science storytelling across digital channels, supporting marketing efforts, and collaborating with exhibitions to surface digital engagement opportunities in-gallery. Overall, the digital layer is used to give our audience access to science they can’t see when they visit: our collection of 30 million specimens and artifacts, and our research and conservation work. This group also ensures the website expresses the brand values, conveys the experience, and performs the duties of connecting education, institutional advancement, and other departments with their constituents, and gives them tools to transact.

Douglas:

What do you think about reporting into the Marketing and Public Engagement division? It must have some advantages and perhaps some challenges too? And I’m also curious if the Chief Marketing Officer is under yet another VP-level, or reports to the top.

Brad:

The CMO reports directly to the President. In our structure the person closest to digital at the executive level is the Chief Technology Officer - he’s on the same level as my direct supervisor, the CMO. He and his team oversee IT, security, ticketing, and the collections database. My digital team is firmly focused on design, content, and digital engagement. So it’s good to be in public engagement as it’s easier to align with those who work directly with our visitors (exhibitions and guest relations). There are some obvious challenges with trying to integrate the collections microsites, ticketing, and other types of work into the main website. So for users, the ecosystem is fragmented. As well, we’re the only team in the building with a UX designer, so not all of the platforms the institution uses have someone overseeing UX concerns. The good news is we have a great relationship with IT and they’re very supportive. The CTO and I meet regularly and are making good progress to align things for users’ sake. And I’m also fortunate in that my boss likes for me to meet with the President monthly to give him updates on our part of the digital world. That’s rare as a director-level person at the Museum, so I’m grateful for that.

Douglas:

That’s great to hear, and I believe it can inspire others. It’s certainly possible to do really great digital work through strong collaboration with the rest of the organization. Leadership is not always about titles and hierarchy or about which department head you report to, but instead can be about effective contributions and working well across the enterprise - sharing the expertise you have with the entire organization for mutual benefit.

Brad:

You and I have had great discussions about strategy - both at the institutional level and within digital. I’m curious about how Mia aligns staff and projects with strategy - how does that unfold at Mia?

Douglas:

Digital at Mia is driven by two very simple yet powerful core strategies: (1) Delight Customers and (2) Help People. Seriously - everything we do has to be fulfilling one (or ideally both) of those elements. Delighting customers applies both to excellence in satisfying internal staff needs and providing top-notch digital experiences for museum audiences. Helping people is likewise both internal and external, from help desk to digital interfaces designed to engage and support visitors as they participate with the museum. In both cases, people are considered primary, not the technology. MAT is dedicated to making sure that people are able to accomplish their goals and have wonderful experiences. By putting people first, all staff in MAT know exactly how to prioritize their work.

This approach aligns well with the museum’s mission and its current strategic plan. We simply do not - ever - chase technology or digital projects unless they are clearly in support of both.

As I recall, you’ve developed clear guiding principles for your team at the Field, right?

Brad:

We have. But first, I have to tell you how much I’ve always loved your two core ideas of delighting customers and helping people. That needs to be a book. The idea of “delight” is so often absent from conversations, but it is an essential part of creating an environment where people can learn and feel inspired.

Douglas:

I should be totally honest here and say that the concept of first-and-foremost delighting customers isn’t my original idea - it’s attributed to

Warren Buffett. He once said he’s not likely to remember the price of the car he bought a few years ago, but he is likely to remember the experience he had with the person who sold it to him. I think that lesson applies equally in our sector. Sorry to interrupt! Let’s go back to your guiding principles.

Brad:

No problem! Yes, our Guiding Principles exist to keep the team oriented and keep projects on the rails. We like to test them frequently. They evolve at the behest of changing business or audience needs, and only with specific intention. We shouldn’t be afraid to say ‘no’ to some projects or ideas. We should be flexible enough to see a good new opportunity but we should say yes to projects and ideas for the right reasons.

- The Museum mission, position, and values inform everything we do

- Objects are objects; only their stories are interesting to real, living, breathing people. When we share objects with our audience, always bring them the story. Show them why this matters

- Vigorously defend science and the scientific process; earnestly believe in the importance of museums

- Balance the need to support digital and traditional advertising and public awareness needs, and the need to proactively, relentlessly innovate in the digital space

- Back decisions with data; prioritize audience needs

- All efforts meet minimum accessibility requirements and to the greatest extent possible, exceed those expectations to create experiences that are open and available to audiences with a broad array of accessibility challenges

- Efforts aimed at visit and logistics planning are inclusive of the needs of individuals from a broad variety of spoken languages and socio-economic backgrounds

Let’s talk about the concept of digital strategy. When you feel your ear tingling, that’s me talking to my colleagues about your framework of digital being a horizontal, not a vertical.

Do you have a specific digital strategy at Mia?

Douglas:

At Mia, digital is simply part of the fabric of the organization. That’s the essence of me describing what we do as a horizontal and not a vertical. To that end, there is no stand-alone digital strategy, neither as a document nor as a set of practices. There is a museum strategy, and digital permeates that to the extent that it will delight customers; of course, there are plenty of museum activities that are non-digital, and at Mia this presents no conflict whatsoever. As long as we can show that customers are delighted, any initiative will move forward, digital or not.

This philosophy has a major impact on talent strategy within MAT and across Mia. For the Media and Technology division, it is critical to hire and retain staff who see the bigger picture and apply their digital and technical talents to support the overall strategic plan and the two core strategies of MAT. Across the museum, it is vital to hire and retain staff who embrace digital as one of the effective tools to use to delight customers. Cross-functional teams can then make the best decisions on what projects or products move forward.

Do you maintain a specific digital strategy at the Field?

Brad:

To be transparent (and in doing so hopefully helpful to others), it’s a work-in-progress. The Museum began a strategic planning process several years before I arrived. My position did not exist and as a result there’s some mentions of technology, but not of a user-driven approach to using digital (tech, channels, content creation methods) to engage our audience during their visit or otherwise, other than a mobile tour app which was already being produced, itself the mandate of a financial gift. I’m in the process of articulating and refining my vision for digital with my boss. Once we feel good about it, I will collaborate with others in the Museum, namely the CTO, to refine and ensure a holistic approach. From there, for the areas I manage, I will take this to my staff and as a team we will discuss and put some stakes in the ground around digital strategy. I want my team to co-write it with me have true ownership. In the next iteration of the Museum’s strategic planning process I aspire to what you describe as not having a document or set of practices, rather to have full integration, permeating the institution.

Douglas:

I realize that you touched on this a bit earlier, but I’d like to follow up a bit. Are you responsible for the full range of digital at the Field?

Brad:

Not exactly. Below are the other departments in the institution that house some form of digital discipline.

Information Technology, which is separate from the digital team, supports the technology infrastructure of the institution including the network, point-of-sale, data security, the enterprise resource management system, online ticketing, and maintains and continually builds out the collections database. This group reports to the Chief Technology Officer, who sits on the executive team. The opportunities for collaboration between digital and IT exist mainly around the integration of the collections database into the primary website, and with the online ticketing system.

The Exhibitions department is similar to the digital team in that both are designing for the general public. They have the same end-user. They design and build the interactives that live in-gallery, as well as the digital wayfinding stations. This group also produces other media elements for exhibitions including video and sound design.

Other Digital Efforts at the Field include

- Digital Learning Manager in the Learning Center

- Staff Photographer located in Science & Education

Douglas:

You also spoke earlier about collaboration between those areas. How do you work together effectively? Are there tips and tricks for doing that really well?

Brad:

It’s been important for us to empower and connect individuals below director level so they have autonomy and decision-making ability. It’s been tricky to navigate because not all directors will send their people to meetings instead of themselves, so I have to manage that. But I find there is so much knowledge and smart thinking by the mid- and junior-level staff—and often deeper insights into problems—that to the extent we can empower and unleash them, it benefits the Museum.

Douglas:

I agree whole-heartedly about the (usually untapped) knowledge and skills that exist in the staff across all hierarchical levels of an organization. Unleashing that potential can be a path to success, especially when we enable people to work together.

Brad:

From my outsider’s perspective, you have the opportunity to create collaboration differently, by virtue of how Mia - and your team specifically - are structured. Can you talk about how collaboration works at Mia?

Douglas:

At Mia, we believe that collaboration is vital to the success of modern organizations. Let me take a step back and set some context. I think two things laid the groundwork for challenging the traditional, siloed organizational structures of museums: digital transformation and changing workforce expectations. Digital was perhaps the first externally-driven force that had a significant impact on all of the museum silos. As we are discussing here, museums are still struggling with where to “put” digital, and most tried to make it just another silo - but the very nature of technology has been to permeate every aspect of organizations and institutions. To the second point, the modern day workforce is very different than preceding generations. We are all knowledge workers, not drones doing repetitive tasks. And knowledge workers expect to have a say in what they focus on (initiatives) and how they do their work (methods). That requires a flatter, non-siloed org structure and cross-functional collaboration the likes of which museums have never really seen before.

At Mia, we have a disciplined approach to collaboration, so that projects get done quickly and effectively. It starts with leadership commitment to a collaborative work environment where staff work together toward common goals that are aligned with the strategic plan. We strive for these teams to be self-organized and to have decision-making authority. Of course, not every effort requires a cross-functional team. We look at the following factors to see when a cross-functional team will succeed:

- Team is responsible for a specific task or deliverable.

- The goal needs different perspectives in order to be achieved.

- Staff with different expertise are needed to work together toward a common goal.

- We can disregard hierarchical level within the organization - get the skills needed, period.

Every cross-functional team has an Executive Sponsor, and the core team is purposefully kept small, ideally around 5 individuals. The team works best if there is in addition a single “initiative owner”, who has the knowledge, authority and availability to support the team’s work.

I don’t intend to make this sound easy or simple. It’s admittedly a work in progress that requires continual review and improvement. Cross-functional teams face plenty of challenges, including:

- Transforming diverse input into one cohesive final output.

- Competing demands may seem contradictory. To reduce this risk, it is important to define roles and expectations for team members and their managers from the very beginning.

- Prioritization conflicts: team goals versus usual day-to-day work tasks.

- Coping with staff who don’t buy into the model 100% — especially unit-level managers who may resent having “their people” pulled onto projects that they don’t “own”

I feel like I’ve gone down the rabbit hole a bit there, but I thought it might be informative.

Let’s see if we can wrap this up - what do you see as the future of digital in our sector - or, to put it another way, if we were to have this conversation a few years from now, how would it be different?

Brad:

I love these types of questions. I’m fascinated with how much more digital is naturally integrated into the lives of workers coming into the workforce now than it was for us. It’s natural and goes without saying. I think this is a huge advantage in our field. I regularly try to be aware of blind spots I may have and ensure I’m open to, and hearing what my team has to say about the use and consumptions patterns of people today. So to that end, what effect will this have when our younger workers are themselves the leaders of institutions? I think your notion of digital thinking being woven into the fabric of the entire institution will be more likely to naturally occur. I think a result of that might likely be a workforce that more readily implements or adapts workflow solutions that are more efficient, fast-moving, and flexible than in the past. Leadership may be more able to step aside in some ways that right now feel unnatural or threatening.

Douglas:

I think we are on a similar wavelength. I have been known to joke that one of my goals is to eliminate my position. I realize that’s a bit of provocation and an oversimplification; what I’m really getting at is my hope that “digital” isn’t really a “thing” in the near future. Organizations won’t have to discuss where to put it because it won’t be seen as an “it” - digital will simply be a given part of all activities. I don’t deny that there will be a need for software developers and technicians, because there will be a need to make new things and to maintain existing things. Perhaps the analogy would be electricity (and credit goes to colleague and friend

Koven Smith, who uses this same analogy and probably more effectively than I do here). There was once a time when organizations were adopting electricity, and they probably needed a Department of Electricity and a Chief Electricity Officer to oversee it. But over time electricity became such a norm that today we basically take it for granted. We still need electricians, we still need electrical engineers, and there is still innovation going on around all things electrical, but it’s not a mysterious or magical thing anymore. It just is. That’s my hope for digital, plain and simple. So in a few years we basically wouldn’t have this conversation at all! However, it is my hope that we will have other conversations in it’s place.

Brad Dunn tweets as

@badunn

Douglas Hegley tweets as

@dhegley

Interested in sharing your own perspectives on these topics? Please tweet at us, or post in the comments below. Thanks!