Powerful stuff. And topics that I've been thinking about for some time as I've worked hard to evolve my own leadership practice. I think that Mike and I agree on the human-centered part - in fact I've built my nonprofit career on working hard to find the best ways to bring people and digital together within our sector to drive positive change, reach more audience, open the doors to our institutions, increase transparency and ultimately help cultural heritage thrive. I've had ups and downs for sure, but my commitment to people will never waver. Every day I apply all that I absorbed during my graduate studies in clinical psychology to recognize people as individuals and help them apply their talents and hard work in the most-effective ways.

In this post, I'd like to zero in on organizational structures. It's a topic that I often address when I'm speaking in public about leadership and innovation. As a connection to my long-ago clinical training, there is a sort of "physician heal thyself" theme here. That is, "The moral of the proverb is counsel to attend to one's own defects rather than criticizing defects in others" credited to Hirsch, Kett, Trefil (2002). The hard work of becoming a social organization connected to our communities must begin with a hard look in the mirror and new ways to imagine ourselves as a type of collaborative community. And a community is built on connections.

|

| Source: https://www.cmu.edu/joss/content/articles/volume6/TsvetovatCarley/net50_6.jpg |

Yet, traditional leadership models have been extremely hard to shake. Even where I work, at Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia), we’ve got one of these diagrams (your place of work probably has something similar).

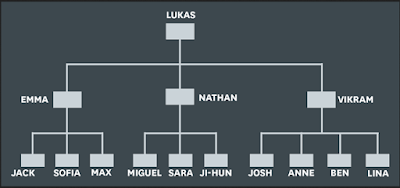

As you can see, there's clearly a boss at the top, then a few silos have been set up, each with its own senior manager, then a list of functions that must be staffed. Pretty standard stuff. But I have a question to ask: what’s the difference between the diagram above and the one below?

I mean, really, what's the difference? Aside from titles and the number of boxes and other picayune details. Both of these so-called "rake" diagrams represent the detailed version of the old, classic pyramid structure. This way of conceptually an organization expresses a clear power relationship and specifies centralized control. Tradition!

Then again, let's just admit that our traditional model of “leadership” is thousands of years old!

So, my next question: is this really what we need in our organizations? Do we think of our staff as unruly peasants who must be dominated and controlled by vigilant stewards who answer only to nobles and royals? In fact, there is plenty of research and writing that this kind of structure has proven to be counter-productive in today's era of the knowledge worker.

We don't have any peasants! We do have extremely smart and dedicated staff, all of whom have ideas about how we could best be providing delight to our customers. We take the time to hire the best people we can find - but then we express in our structures that they are of lesser value than anyone else. Ugh.

Museums and other cultural heritage organizations can evolve. To be honest, the small world networks already exist, the challenge for leadership is to encourage, support and activate that network. Here is a very simplified but real-world example of our most vital resource: our PEOPLE. People are the network nodes, and people often work on more than one team. Those people – and the connections between teams – create a small world network. The closer the connections, the higher the effectiveness of the entire organization.

Small world networks matter, in practical and realistic ways. Let's examine this from one particular angle: who in your organization is best-positioned to make change?

In a traditional pyramid structure, power is concentrated at the top (in the example below, culled from the Harvard Business Review, that would be Lukas). In comparison, people at the bottom of the stack like Jack or Sofia are each just one of the minions. The organization in this case would expect Lukas to be the agent of change. After all, he's got the responsibility and the power, so he must be able to push for change. Everyone else should just fall in line - they report to him!

So where does this lead us? I'd like to share a bit about some of the ways that we've been re-conceptualizing our org structures here at Mia, specifically for the Media and Technology Division (for which I am held responsible). We've got our standard rake diagram, which shows who's in which department and who reports to whom. Pretty standard HR stuff, right. But it also conveys a number of the issues that Mike Murawski explored in his post: explicit and implicit power relationships, hierarchy, silos, value, etc. Clearly, as you can see:

I am the lord of all I survey - you shall obey!But wait, I don't think of myself as a lord at all. And the staff within the MAT division is outstanding - dedicated, smart, capable, and each with specific knowledge that I simply do not possess. They know far more about their specific jobs and how to do them than I ever will. Why would I ever even attempt to demand obedience? We are going to be so much more successful when they set their own goals, their own working methods and establish their priorities - and do so with one another through conversation and consensus based on the mission and strategic plan. My real job is to foster that conversation, not to bark out orders. So if this diagram is not an accurate depiction of how it all works, I've been trying to think of other ways to describe MAT and the way we work.

One version is this set of concentric circles (below). Now we see the focus on our core strategy, which has two key principles: Delight Customers and Help People. Everything that we do aligns with those core principles. Then as we move outward, we can see how we deliver on those core strategies, what we actually deliver (sorry about some internal lingo in that ring), and finally the names of people lined up with their primary areas of focus.

By using this concentric ring approach, we've begun removing the hierarchy (akin to the "flower" diagram from Oakland Museum of California described in Mike's post). The MAT division appears to be one team, all working toward shared goals. No single person is indicated as more important or more powerful than another - all have value, all have important contributions to make.

But still there's something missing. Like the small world network - the connections between people and projects, the impact they have on each other. And then there is an element of reality that gets swept under the rug with this diagram: no matter how we wish we could deny it, power is a real thing, it exists in every group of people, and it is formalized in titles, supervisory relationships, years of experience, etc. To pretend that everyone is somehow exactly the same on every measure is to be naive, or worse yet delusional. Hmm.

One day when thinking about the mutual impact we all have on each other in the workplace, I started thinking about power as a kind of gravity. Everyone in the workplace has some degree of power. That power might come from obvious variables I listed in the paragraph above. Or it could be related to any number of other variables, some potentially unconscious: gender, height, accent, background, race, age, attractiveness, extroversion/introversion, role, knowledge, etc. The bottom line is that we all size each other up all the time, and we make snap judgements about power, with and without even knowing it. Power has a kind of gravity, in each of us.

Please bear with me here, I realize this is a bit of a reach and the analogy isn't perfect - but I ended up thinking about asteroids

Asteroids are bodies, in motion. They have direction, but they are also pulled and pushed by the gravity of other bodies. The sun sits at the center of the solar system, and the asteroids orbit around it. There are planets that are also in orbit, and the gravity of the planets influences the path and movement of each and every asteroid, as well as that of other planets. Finally, asteroids influence each other. They pass by, rotate around each other, they even collide sometimes. Bigger asteroids exert more influence, but even a smaller asteroid can subtly re-direct a bigger one. Of course, proximity plays a part, the closer one body is to another, the more intense the influence.

I think this can work, at least to some degree, as a way to see our work places. The sun is the mission and vision, the planets are the ambitious activities we take on, and we are all asteroids, dancing around and bouncing off one another while we speed around trying to stay on course.

Seen from this lens, even a short conversation with an intern might actually steer me in an entirely new way that I would never have considered on my own. And vice versa. That indicates mutual influence, while recognizing that each individual has unique characteristics, including power.

I recognize that there is so much more that could be explored on this topic. For instance:

- How to diagram the small world networks?

- How to conceptualize the ebb and flow of those networks and their multiple relationships?

- How to think about the Butterfly Effect - the idea that even very small events can lead to large and unanticipated outcomes?

- and more ...

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated. Comments that include links/URLs will generally be rejected, unless the link is to well-crafted, related content.